Abstract

This study examines the interplay between luxury fashion and consumer emotions focusing on how tailored feedback, centered on exclusivity or sustainability, shapes feelings of pride and subsequent consumer behavior. Using an experimental design with 394 participants, the research distinguishes between hubristic pride, associated with superiority and exclusivity, and authentic pride, tied to accomplishment and socially responsible choices. Findings reveal that feedback emphasizing exclusivity significantly heightens hubristic pride, which in turn drives positive word-of-mouth intentions, particularly for new luxury purchases. While feedback emphasizing sustainability does not significantly enhance authentic pride, authentic pride strongly drives positive word-of-mouth intentions, regardless of whether the purchase is second-hand luxury fashion or new luxury fashion. Overall, the study provides valuable insights for tailoring communication strategies and highlights the challenges of effectively communicating sustainability in luxury fashion.

Introduction

The fashion industry's environmental impact is largely driven by fast fashion, which emphasizes rapid production, mass consumption, and short-lived trends (Sharma, 2021; Powell, 2021; Centobelli et al., 2022). While slow fashion promotes ethical production and circularity (Carey & Cervellon, 2014; Jung & Jin, 2016), consumer demand for luxury fashion is also growing, as luxury fashion products are becoming more accessible to a wider audience (Aleem et al., 2024). Luxury is strongly associated with high quality and durability (e.g., Tynan et al., 2010), aligning with sustainability principles (De Angelis et al., 2017). Its longer lifespan and resale potential contribute to a more circular consumption model (Jung & Jin, 2016; Yu et al., 2023).

Additionally, the second-hand luxury fashion market is expanding rapidly (Jebarajakirthy et al., 2020), offering a simpler and more transparent path to sustainability by bypassing the complexities and risks of eco-fashion certifications and claims. This creates a circular consumption cycle, where some consumers purchase new luxury items and later resell or donate them, while others buy pre-owned luxury fashion. This cycle supports a more sustainable fashion model that contrasts sharply with the disposable nature of fast fashion.

While slow fashion promotes sustainability, the effectiveness depends on consumer adoption and behavior change, emphasizing the need to understand what motivates consumers to embrace such practices. Emotions, in particular, play a pivotal role in shaping these decisions (e.g., Davies, 2015; Eckhardt et al., 2010; Gwozdz et al., 2017; Guedes et al., 2020; Jung & Jin, 2016). Of the myriad emotions influencing consumer behavior, pride uniquely combines personal achievement and social recognition (e.g., Bly et al., 2015; Antonetti & Maklan, 2014; Antonetti & Maklan, 2014), making it especially impactful in contexts where social status, such as luxury and ethical considerations such as sustainable fashion intersect (Shi et al., 2024; Septianto et al., 2020; Pangarkar et al., 2023).

However, while sustainable fashion is associated with authentic pride (e.g., Adıgüzel & Donato, 2021; Antonetti & Maklan, 2014; Antonetti & Maklan, 2014), stemming from the belief that one has achieved something through effort or made a socially responsible choice (Tracy & Robins, 2007), luxury fashion is often linked to hubristic pride (e.g., McFerran et al., 2014; Septianto et al., 2022; Shi et al., 2024), which arises from the belief that one is deserving something due to a sense of superiority over others. Both facets of pride are linked to social status and, therefore, expected to increase the willingness to share information (Tracy & Robins, 2007). Willingness to share information is highly valuable in marketing because it leverages consumers' authentic experiences and social influence and is perceived as more trustworthy than traditional advertising (Ho & Dempsey, 2010). Because pride is especially strong when others are aware of one's achievements (Verbeke et al., 2004) consumers' feelings of pride may be increased by giving them positive feedback on their purchases (Pham & Sun, 2020). Given that luxury fashion is linked to both exclusivity (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009) and sustainability (De Angelis et al., 2017), the way feedback emphasizes these values could influence consumer engagement differently depending on whether the purchase is new or second-hand."

Although previous studies have examined the role of pride in luxury consumption (e.g., Septianto et al., 2020; Septianto et al., 2020; Adıgüzel & Donato, 2021; Shi et al., 2024) as well as the influence of feedback on consumer decision-making (e.g., Chiang et al., 2014; White et al., 2019), little is known about how feedback emphasizing different values, such as exclusivity versus sustainability, affects the dual facets of pride (hubristic and authentic) and their subsequent influence on consumer behavior. Furthermore, existing studies have not differentiated between the effects of feedback on new versus second-hand luxury purchases, which are increasingly relevant in today’s circular economy. This gap highlights the need for a nuanced understanding of how targeted feedback can shape consumer perceptions and behaviors in distinct segments of the luxury market, particularly as consumer demand for luxury grows.

To address this gap, this study investigates the following research question: How do tailored feedback mechanisms centered on exclusivity or sustainability influence pride (hubristic vs. authentic) and subsequently drive positive word-of-mouth in the context of new versus second-hand luxury fashion consumption?

Theory

Recently, there has been a surge of interest in the luxury fashion sector among academics and practitioners, leading to a rapid expansion of research in this field (Aleem et al., 2024). The luxury fashion market is undergoing significant transformations, including the rise of “new fashion,” associated with increasingly younger and digital native consumers and driven by the growth of non-Western markets (Khan, 2015). Additionally, new luxury segments, such as “masstige,” are emerging, referring to mass-produced goods marketed as luxurious or prestigious (Bilro et al., 2022). At the same time, consumer values are shifting toward sustainability and responsible consumption (Amatulli et al., 2020), exemplified by trends like “second-hand luxury,” which is growing rapidly (Jebarajakirthy et al., 2020). Overall, these markets present a more sustainable alternative to fast fashion by promoting garment longevity and reducing waste, aligning with principles of slow fashion. This dual focus on exclusivity and sustainability in luxury fashion has created challenges for marketers (Aleem et al., 2024). Exclusivity appeals to consumers' desire for differentiation and social status (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009), while sustainability resonates with growing ethical concerns among consumers (Amatulli et al., 2020). This evolving landscape highlights the need to explore the emotional and psychological factors that drive consumer behavior in both new and second-hand luxury fashion segments, offering insights into how brands can effectively navigate these shifting dynamics.

Pride in Luxury Fashion Consumption

While numerous definitions of luxury goods have been proposed over time (Kapferer et al., 2017), this study adopts the modern yet comprehensive description by (Tynan et al., 2010), who define luxury as products and services of superior quality, priced at the higher end of their category, but still accessible. Because of their premium quality and prices, consumers are motivated to purchase luxury goods as a way of demonstrating social status and self-enhancement (Belk, 2011; Tynan et al., 2010) further emphasize that luxury brands are not solely about the products themselves but also about the emotional experiences they evoke. This aligns with recent studies linking luxury consumption to positive emotions, particularly to the pleasant feeling of pride (e.g., Septianto et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2024).

Pride is a positive and adaptive emotion that reinforces actions leading to socially valued outcomes (Williams & DeSteno, 2008; Tracy & Robins, 2004). There are two types of pride: hubristic pride, associated with narcissism and arrogance, and authentic pride, linked to accomplishment and confidence (Tracy & Robins, 2007). In consumer behavior, sustainable fashion tends to evoke authentic pride (Adıgüzel & Donato, 2021; Shi et al., 2024; Islam et al., 2022), as consumers feel they are making a responsible or meaningful choice (Tracy & Robins, 2007). In contrast, luxury fashion tends to evoke hubristic pride (McFerran et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2024), driven by feelings of superiority over others (Tracy & Robins, 2007). Recognition by others amplifies pride as it serves as a social marker of personal value, particularly for achievements linked to social status (Verbeke et al., 2004; Williams & DeSteno, 2008). This recognition motivates consumers to share their experiences, a key behavioral response to pride (Berger & Milkman, 2012; Fredrickson, 2001; Tracy & Robins, 2007).

In marketing, this sharing behavior is referred to as word-of-mouth, which typically stems from a positive perception of the product and a desire to encourage others to try it (Westbrook, 1987). In the context of luxury fashion, the role of pride, particularly authentic pride, has been closely linked to positive word-of-mouth enchantment (e.g., Adıgüzel & Donato, 2021; Pangarkar et al., 2023; Septianto et al., 2020; ). Pangarkar et al. (2023) propose that authentic pride encourages word-of-mouth behavior among sustainable luxury consumers, especially when it aligns with their values. Septianto et al. (2020) argue that consumers are more likely to engage in positive word-of-mouth about sustainable fashion when the consumption of such products evokes feelings of authentic pride. However, their findings reveal that this is more effective when the luxury dimension of sustainable luxury is heightened. This suggests that triggering hubristic pride, even in sustainable luxury purchases, may boost word-of-mouth intentions. While hubristic pride has recently been linked to negative word-of-mouth behavior (Septianto et al., 2022), it can also drive positive word-of-mouth due to its strong connection to public differentiation and social validation (Tracy & Robins, 2007). This duality highlights how both forms of pride can encourage consumers’ willingness to share information about a purchase or product, offering a valuable strategy for promoting luxury fashion. From this, the following is posited:

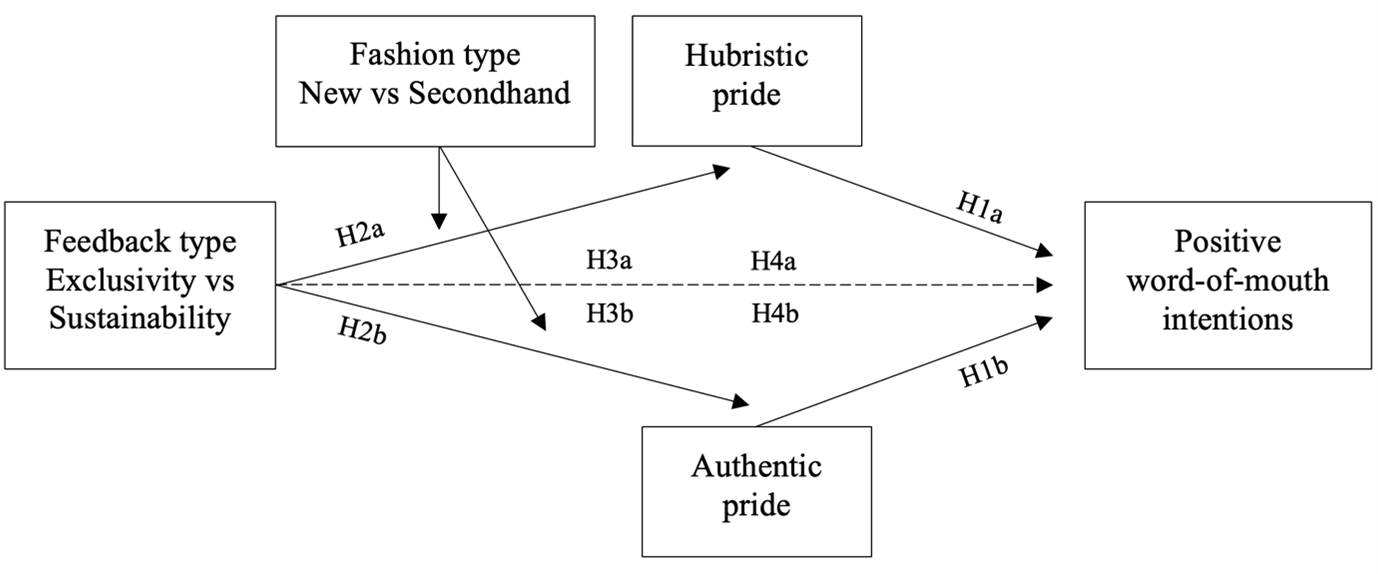

H1a: Hubristic pride will enhance positive word-of-mouth intentions.

H1b: Authentic pride will enhance positive word-of-mouth intentions.

The Effect of Feedback on Hubristic and Authentic Pride

From a framing perspective (Entman, 1993), how feedback is structured and communicated can influence how individuals perceive their actions and outcomes. By selectively emphasizing certain aspects of information, framing shapes consumer interpretations and emotional responses. Accordingly, marketers can amplify consumers’ sense of pride by offering tailored feedback on the positive outcomes of their actions (Pham & Sun, 2020). Feedback is specific information provided about an individual’s performance or behavior (Lehman & Geller, 2004). It usually consists of information about the actual effect of individuals' actions and is expected to be more successful when tailored to suit a particular situation (Lehman & Geller, 2004). However, for change to occur, feedback must be combined with a reinforcing consequence, such as praise or incentives, to make an effective intervention (Daniels & Bailey, 2014). Several studies have suggested that feedback can be used to effectively change consumer behavior (e.g., Chiang et al., 2014; White et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the way feedback is framed can significantly influence how consumers interpret and respond to it. From a value-framing perspective (Schwartz, 1992), feedback that emphasizes exclusivity reinforces self-enhancement values such as status and power, aligning with hubristic pride. In contrast, sustainability-focused feedback appeals to universalism and benevolence values, which resonate with authentic pride. By tailoring feedback to align with both consumers’ values marketers can enhance the emotional impact of their messaging, reinforcing either hubristic or authentic pride.

This distinction is particularly relevant in luxury consumption, where self-enhancement and ethical considerations often intersect. In luxury fashion, exclusivity is a critical value (Jung & Jin, 2016; Kapferer & Bastien, 2009), as it supports social status and self-transformation, making consumers feel special and distinct from others (Kapferer et al., 2017). As a result, luxury fashion communication has traditionally emphasized exclusivity, aligning with consumers’ desire to demonstrate social status (Belk, 2011). In line with this reasoning, this study posits that communication focusing on exclusivity and superiority in luxury fashion will resonate with these values, thereby increasing hubristic pride. Thus, the following is proposed:

H2a: Feedback focused on exclusivity (vs. sustainability) in luxury fashion purchases enhances hubristic pride.

However, while luxury fashion consumers are becoming more responsible (Amatulli et al., 2020) marketers face challenges in integrating sustainability into their communication strategies (Aleem et al., 2024). (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009), express concerns that promoting sustainability in luxury branding could conflict with the traditional ethos of luxury goods, which often emphasize the dream of exclusivity. Septianto et al. (2020) argue that luxury brands can be perceived as either exclusive or authentic, with European luxury brands often focusing on history and tradition (i.e., authenticity), while American luxury brands emphasize unique storylines (i.e., exclusivity). The concept of authenticity, rooted in maintaining product quality and transparency about production practices, aligns with the values of slow fashion. Recent research highlights that the authenticity of fashion products and business processes is key when brand managers aim to position their brands as sustainable (Bandyopadhyay & Ray, 2020). In line with this reasoning, this study posits that communication emphasizing the authentic sustainability attributes of luxury fashion, such as premium quality and ethical production, will resonate with consumers' values, thereby increasing authentic pride. Thus, the following is proposed:

H2b: Feedback focused on sustainability (vs. exclusivity) in luxury fashion purchases enhances authentic pride.

Drawing on the assumption that feedback tailored to emphasize exclusivity can magnify feelings of hubristic pride, while sustainability-focused feedback aligns with authentic pride, both of which are pivotal in fostering positive word-of-mouth and sustainable consumption patterns, this study proposes that pride mediates the relationship between feedback and word-of mouth intentions:

H3a: Feedback focused on exclusivity (vs. sustainability) in luxury fashion purchases enhances positive word-of-mouth intentions through hubristic pride.

H3b: Feedback focused on sustainability (vs. exclusivity) in luxury fashion purchases enhances positive word-of-mouth intentions through authentic pride.

The Role of New Versus Second-Hand Luxury Fashion

The marketing of luxury goods is inherently complex, requiring a balance between satisfying consumer demand and maintaining exclusivity (Tynan et al., 2010). The luxury fashion sector is currently undergoing significant changes, with a notable rise in second-hand markets (Jebarajakirthy et al., 2020). This shift presents both challenges and opportunities: while second-hand markets may reduce the demand for new luxury goods, they also create opportunities for brands to integrate second-hand products into their business models, catering to a growing market of sustainability-conscious consumers (Aleem et al., 2024).

Both new and second-hand luxury items are linked to exclusivity and sustainability, but in distinct ways. New luxury fashion often symbolizes exclusivity, high social status, and self-enhancement, aligning with consumer desires for differentiation and social validation (Belk, 2011; Kapferer & Bastien, 2009; Kapferer et al., 2017). In contrast, second-hand luxury fashion is increasingly associated with sustainability, ethical consumption, and the preservation of valuable goods, resonating with consumers’ growing concern for environmental impact and social responsibility (Amatulli et al., 2020; Jebarajakirthy et al., 2020).

This study proposes that the effects of feedback will differ depending on the type of luxury fashion purchased. Feedback emphasizing exclusivity for new luxury items aligns with the desire for social status and differentiation and is more likely to enhance hubristic pride. On the other hand, feedback emphasizing sustainability for second-hand luxury items reinforces the consumer's ethical values, fostering authentic pride. From this, the following is posited:

H4a: Feedback focused on exclusivity (vs. sustainability) in new (vs. second-hand) luxury purchases enhances hubristic pride, leading to increased positive word-of-mouth intentions.

H4b: Feedback focused on sustainability (vs. exclusivity) in second-hand (vs. new) luxury purchases enhances authentic pride, leading to increased positive word-of-mouth intentions.

Method

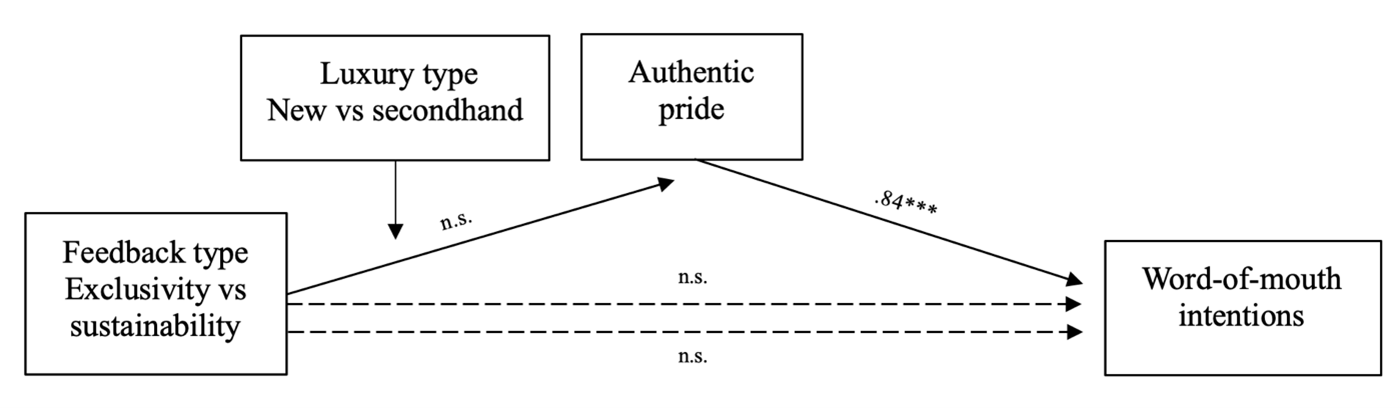

A pre-registered experimental study was conducted to test the hypotheses regarding the influence of pride on consumer behavior in luxury fashion purchases. Figure 1 presents the conceptual model and hypotheses for the current research, illustrating the relationships between feedback, types of pride, and word-of-mouth intentions.

Sample, Design, and Procedure

The study was designed using Qualtrics, and the data was collected in controlled environments using Prolific. Four hundred and eight U.S. respondents aged 18-70 participated in the study. To ensure data quality, two screener questions were enforced as attention checks. In the first attention check participants were asked to answer a simple math question: “What is 3 + 5?” and were then randomly given five alternatives to choose from: “3, 5, 8, 10, 13 and 15”. In the second attention check participants were asked to select which product they had been exposed to in the study. Respondents were randomly given five garments to choose from. The five alternative items in the attention check were a jacket, a sweatshirt, jeans, shoes, and a T-shirt. Nine respondents were removed due to failure to pass the attention tests, while another five were removed due to invalid ID numbers, resulting in a total of 394 remaining valid responses. In terms of gender distribution, 37,30% were men, 61,40% were women, 5% identified as “non-binary / third gender”. The mean age of the respondents was 37.65, with a standard deviation of 11.77.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions, according to a 2 (new luxury fashion product vs. a second-hand luxury fashion product) x 2 (feedback on exclusivity vs. feedback on sustainability) between-subjects design. Participants first answered questions about their gender and age. Then, they were instructed to imagine buying a pair of luxury jeans. Jeans was chosen as representing the luxury product because of its unique position in luxury fashion where it is spread among all type of classes (Bellezza & Berger, 2020). The two pair of jeans were framed in the descriptions as; luxury denim, brand new (see Figure 2) or second-hand denim, pre-owned (see Figure 3). Both pair of jeans looked identical and had the same descriptions (e.g., product details, size, fit, delivery and returns) and prize. To make the experiment as authentic as possible, it was designed to resemble a natural online environment based on the layout usually found in online stores selling luxury clothing.

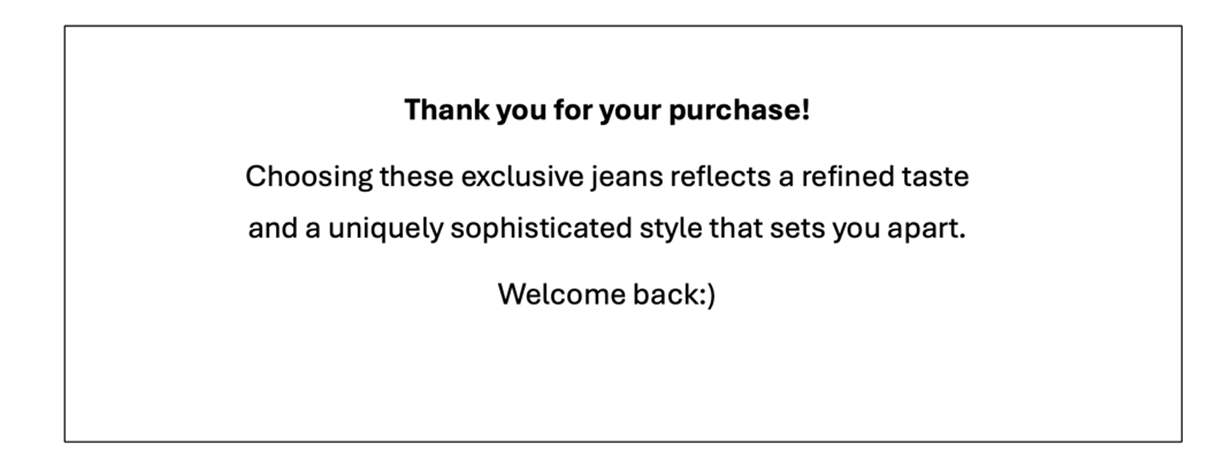

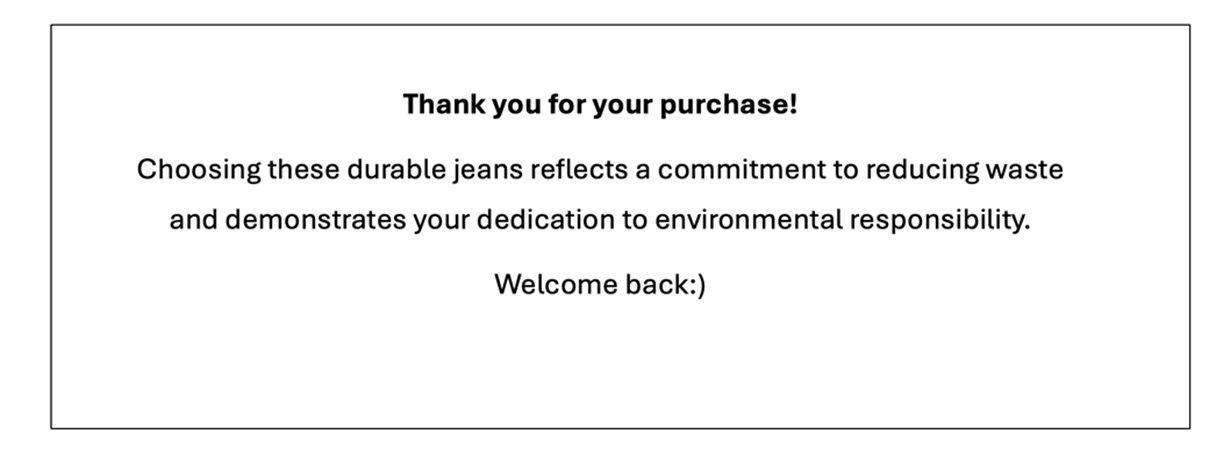

After the imaginary purchase, the participants were given feedback that thanked them for their purchase and welcomed them back. The feedback varied across the four experimental conditions (i.e., type of jeans and feedback). The two groups in the exclusivity feedback condition got feedback telling them that their choice of exclusive jeans reflects a refined taste and a uniquely sophisticated style that sets them apart (see Figure 4). The two groups in the sustainability feedback condition received feedback telling them that their choice of durable jeans reflects a commitment to reducing waste and demonstrates their dedication to environmental responsibility (see Figure 5). This kind of feedback is commonly practiced in offline and online stores. The respondents were roughly equally distributed among the four groups.

Measures

To assess the effectiveness of the experimental manipulation, participants were asked to rate the feedback they received in terms of its ability to convey a sense of exclusivity and sustainability for the jeans. The feeling of authentic pride was measured using four items, of which two were adapted from (Tracy & Robins, 2007) authentic pride scale (Item wordings: I feel proud based on the purchase I have made”; “I feel accomplished based on the purchase I have made”). The first item was chosen because proud is the term most related to pride, and the second because accomplished is the term strongest related to authentic pride and the least connected to hubristic pride in the full pride scale (Tracy & Robins, 2007). The authentic pride scale has previously been used in studies on pro-environmental behavior (e.g., Adıgüzel & Donato, 2021; Onwezen et al., 2013; Shi et al., 2024). The two other items were adapted from (Roseman, 1991) and modified to fit the current context (Item wordings: “I feel good about myself based on the purchase I have made”; “I feel pleased based on the purchase I have made”). These items have previously been used in sustainable consumption research (e.g., Antonetti & Maklan, 2014; Antonetti & Maklan, 2014). The feeling of hubristic pride was measured using four items adapted from (Tracy & Robins, 2007) hubristic pride scale and modified to fit the current context (Item wordings: “I feel superior”; “I feel exceptional”; “I feel above others”; “I feel conceited”). The first item was chosen because superior is a term often used when referring to hubristic pride, used in previously studies on hubristic pride and luxury (Septianto et al., 2022), the third because exceptional is the synonym strongest related to superior, the third I feel above others has also been used in studies on hubristic pride and luxury (e.g., Shi et al., 2024), and the last item was chosen directly from the original scale.

Positive word-of-mouth intentions was measured using three items from (Eisingerich et al., 2015). The items measured the willingness to share information with friends and family (Item wordings: “I am likely to say positive things about the product to others in person”; “I am likely to encourage friends and relatives to buy the product in person”; “I am likely to recommend the product to others in person”). Additionally, fashion consciousness was measured. The scale used for measuring the level of fashion consciousness included four items adapted from (Nam et al., 2007) and slightly modified to fit the current context (Items wordings: “It is important for me to be well dressed”; “I usually have one or more outfits that are of the latest style”; “An important part of my life and activities is dressing smartly”; “It is important to me that my clothes be of the latest style”). For all items, the respondent's level of agreement was measured on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

To assess the validity and reliability of the measurement scales, Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted using Principal Axis Factoring with Oblimin rotation. The analysis confirmed a three-factor structure for the independent variables: authentic pride, hubristic pride, and fashion consciousness (see Table 1). Factor loadings ranged from 0.74 to 0.97, and Cronbach’s alphas were above the 0.70 threshold (Cronbach, 1951), indicating strong internal consistency. Authentic pride exhibited consistently high factor loadings (Cronbach’s $\alpha$= 0.95), whereas hubristic pride showed slightly greater variability (Cronbach’s$\alpha$= 0.87), suggesting potential context-dependent differences in its measurement. The reliability scores for word-of-mouth endorsement (Cronbach’s$\alpha$= 0.95) and fashion consciousness (Cronbach’s$\alpha$= 0.91) were similarly strong.

To further validate this structure, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed (N = 394). The model demonstrated acceptable fit indices (CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.05), confirming the distinctiveness of the constructs. However, hubristic pride exhibited greater variation in factor loadings (ranging from 0.52 to 0.89), which remains within an acceptable range (Hair et al., 2010) but suggests that this construct may be more context-dependent and susceptible to measurement variability compared to authentic pride (Paulhus, 1984).

Altogether, these findings validate the distinction between hubristic and authentic pride, while also highlighting the measurement complexities associated with self-reported hubristic pride. Table 1 provides the item wordings, means, standard deviations, factor loadings, and Cronbach’s alphas for all scales used in the study.

| Scale | Item Wording | Mean | SD | FL | CA | C1 | C2 | C3 |

| Hubristic pride | .87 | |||||||

| 1-9 | I feel superior | 3.02 | 1.64 | .92 | .26 | .11 | .87 | |

| 2-9 | I feel exceptional | 3.45 | 1.67 | .81 | .45 | .16 | .70 | |

| 2-9 | I feel above others | 2.83 | 1.60 | .92 | .16 | .08 | .91 | |

| 2-9 | I feel conceited | 3.04 | 1.69 | .74 | -.20 | .09 | .81 | |

| Authentic pride | .95 | |||||||

| 1-9 | I feel proud | 4.44 | 1.62 | .94 | .89 | .21 | .16 | |

| 2-9 | I feel accomplished | 4.72 | 1.59 | .93 | .89 | .21 | .15 | |

| 2-9 | I feel good about myself | 4.72 | 1.56 | .95 | .93 | .18 | .08 | |

| 2-9 | I feel pleased | 4.83 | 1.53 | .92 | .90 | .15 | .07 | |

| Word-of-mouth | .95 | |||||||

| 1-9 | I am likely to say positive things ... | 4.74 | 1.55 | .93 | ||||

| 2-9 | I am likely to encourage friends ... | 4.24 | 1.71 | .96 | ||||

| 2-9 | I am likely to recommend ... | 4.43 | 1.69 | .97 | ||||

| Fashion consc. | .91 | |||||||

| 1-9 | It is important for me to be well dressed | 4.38 | 1.67 | .87 | ||||

| 2-9 | I usually have one or more outfits that are of the latest style | 3.52 | 1.88 | .89 | ||||

| 2-9 | An important part of my life and activities is dressing smartly | 3.92 | 1.73 | .89 | ||||

| 2-9 | It is important to me that my clothes be of the latest style | 3.10 | 1.75 | .88 |

To address common method bias (CMB), several strategies were employed. Psychological separation was employed by structuring the study with sequential tasks. Two types of attention checks were used, and invalid responses were removed to ensure high-quality data. Validated scales, such as those from (Tracy & Robins, 2007; Nam et al., 2007), were utilized for their reliability and clarity. Both pride scales were tested in a pre-study using factor analysis. The survey length was kept manageable to prevent participant fatigue, which can lead to biased responses. Additionally, the time taken by participants to complete the survey was monitored. These measures collectively support the conclusion that CMB is not a significant issue in this study.

Results

To systematically examine the impact of feedback on pride and word-of-mouth intentions, a series of analyses were conducted. First, we verify the effectiveness of the experimental manipulation to ensure that participants perceived feedback messages as intended. Next, we assess the direct effects of hubristic and authentic pride on word-of-mouth intentions. Further, we explore the indirect effects through mediation analyses, followed by moderation analyses to determine whether the effects of feedback differ based on luxury type. Finally, we summarize the key findings to highlight the most critical insights from the results.

Manipulation Check

To test whether the respondents perceive a difference between the exclusivity and sustainability feedback conditions as intended, a one-way ANOVA was conducted. The analysis revealed a significant difference (F = 53.82, p <0.001), in which the group receiving feedback on exclusivity perceived this as more exclusive (M = 5.18, SD = 1.48) than sustainable (M = 4.11, SD = 1.43), while the group receiving feedback on sustainability perceived this as more sustainable (M= 5.73, SD= 1.08) than exclusive (M= 3.76, SD = 1.76).

Demographic and Normality Testing

To ensure equivalency across experimental conditions, demographic variables were examined across the four groups, focusing on gender and age. Normality was assessed with gender as the observed factor. For the group exposed to new luxury denim and exclusivity feedback, skewness was -0.04 and kurtosis was -0.83, indicating a near-symmetric and slightly flatter distribution. The group with sustainability feedback showed a mild negative skew (skewness = -0.32) and a platykurtic distribution (kurtosis = -0.84). The second-hand denim groups also exhibited mild negative skewness and platykurtic tendencies. Despite minor deviations from normality, the data were approximately normal. Levene’s test showed no significant variance violations (p > 0.05), and ANOVA revealed no significant differences between groups on the dependent variable, F(3, 390) = 0.52, p = 0.67, with a very small effect size ($\eta^2 = 0.004$), indicating gender had minimal impact.

For age, mean ages were similar across groups, ranging from 37.47 to 37.86 years. Age ranges varied widely, but normality tests (Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk) were significant (p < 0.05), suggesting non-perfect normality. However, skewness and kurtosis values indicated only slight deviations. Given the large sample size (n = 394), parametric tests remain robust due to the Central Limit Theorem, minimizing the impact of these deviations (Kwak & Kim, 2017). These results confirm successful randomization and group comparability.

Direct Effects of Pride on Word-of-Mouth Intentions

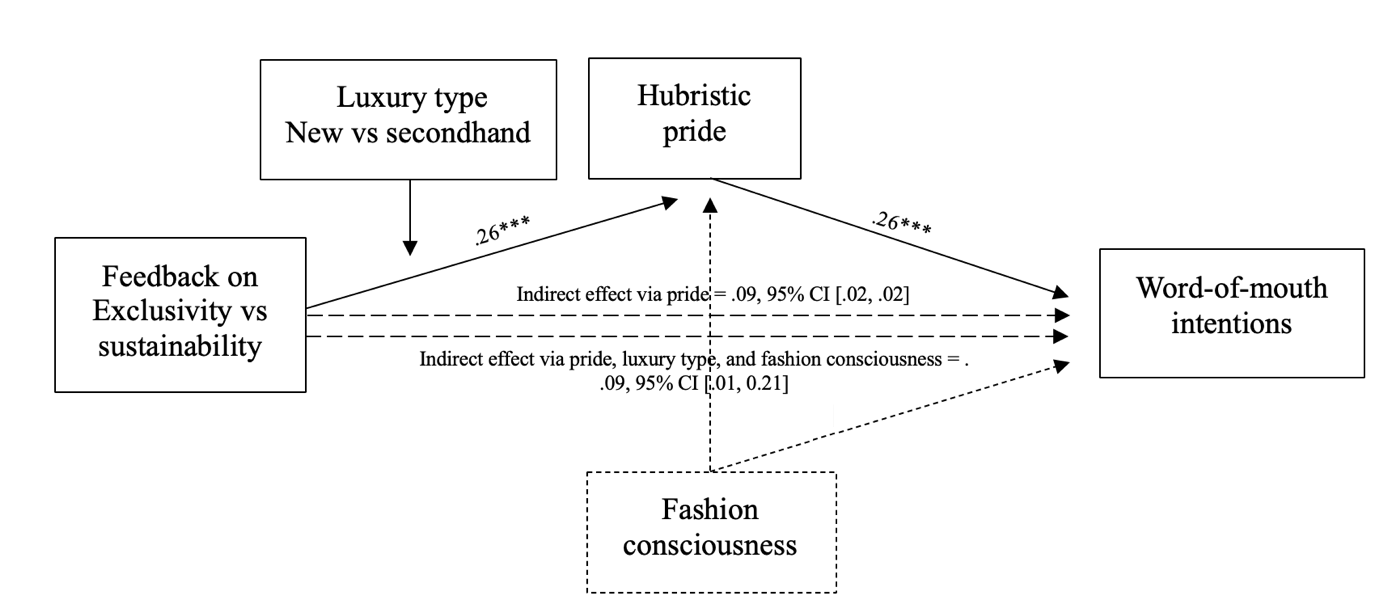

To test H1a and H1b, two separate linear regression analyses were conducted. The first analysis examined the impact of hubristic pride on word-of-mouth intentions, revealing a significant effect (b = 0.26, t(392) = 4.77, p <0.001), suggesting that increases in hubristic pride are associated with increases in word-of-mouth intentions. The overall model was significant (F(1, 392) = 22.74, p <0.001) explaining 6% of the variance (R² = 0.06). To assess whether a similar effect applied to authentic pride, a second regression analysis was conducted. This analysis revealed a significant effect (b = 0.84, t(392) = 3.64, p <0.001), indicating that increases in authentic pride are associated with increases in word-of-mouth intentions. The overall model was significant (F(1, 392) = 638.01, p <0.001) explaining 62% of the variance (R² = 0.62). All significant results are shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Direct Effect of Feedback on Hubristic and Authentic Pride

To test H2a and H2b, whether feedback type (exclusivity vs. sustainability) influences different forms of pride, two T-tests were conducted. The first with hubristic pride as a function of feedback type (exclusivity vs. sustainability). The results showed a significant difference in hubristic pride between the two groups (b = 0.26, 95% CI [0.06, 0.45], t = 2.53, p = 0.007). The mean difference between the groups was 0.35 with 95% CI [0.08, 0.63]. The group receiving exclusivity feedback had a higher hubristic pride (M = 3.26, SD = 1.50) than the group that received sustainability feedback (M = 2.90, SD = 1.26), confirming hypothesis H2a. The overall model was significant (F(1,392) = 6.403, p = 0.012), accounting for 1.6% (R² = 0.016) of the variance in hubristic pride.

To examine whether a similar pattern applied to authentic pride, a second analysis was conducted. The results showed no significant difference in authentic pride between the two groups (b = -0.11, 95% CI [-0.31, 0.09], t = -1.10, p = 0.20). The mean difference between the groups was -0.16 with 95% CI [-0.45, 0.13]. The group receiving sustainability feedback had a slightly higher, but nonsignificant, authentic pride (M = 4.69, SD = 1.39) than the group that received exclusivity feedback (M = 4.52, SD = 1.54 ), not confirming hypothesis H2b. The overall model was not significant (F(1,392) = 1.202, p = 0.274), accounting for 0.3% (R² = 0.003) of the variance in authentic pride. All significant results are shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7.

Mediation Analyses: Indirect Effects of Feedback via Pride

To test H3a, and H3b, whether pride mediates the relationship between feedback type and word-of-mouth intentions, two mediation analyses were conducted using PROCESS Model 4 (Hayes, 2022), with 5,000 bootstrapped samples. In the first model, feedback type (exclusivity, coded as 1, vs. sustainability, coded as 0) was the independent variable, hubristic pride was the mediator, and word-of-mouth intentions was the dependent variable. In the second model, feedback type was again the independent variable, authentic pride was the mediator, pride and word-of-mouth intentions was the dependent variable.

The results of the first analysis showed that feedback type had a significant direct effect on hubristic pride (b = 0.354, p = 0.012), accounting for 2% of the variance (R² = 0.02), reconfirming H2a. Hubristic pride had a significant direct effect on word-of-mouth intentions (b = 0.27, p = <0.001), and the overall mediation model predicting word-of-mouth via hubristic pride was significant (F(2, 391) = 11.43, p < 0.001), accounting for 6% of the variance (R² = 0.06), reconfirming H1a. The indirect effect of feedback type on word-of-mouth intentions through the mediator hubristic pride was significant (b = 0.09, 95% CI [0.0181, 0.0184]). However, the direct effect of feedback type on word-of-mouth intentions (b = -0.06, p = 0.69), was not significant, suggesting that the influence of feedback type on word-of-mouth intentions operates primarily through hubristic pride, confirming hypothesis H3a. The significant mediation effect is shown in Figure 6.

Moderation Analyses: The Role of Luxury Type

Having established that pride mediates the relationship between feedback type and word-of-mouth intentions, we next examined whether this effect varies depending on fashion type. To test H4a and H4b, whether the effects of feedback type on pride, and its indirect influence on word-of-mouth intentions, depend on luxury type, two interaction analyses were conducted using PROCESS Model 7 (Hayes, 2022). The first model assessed how fashion type (new, coded as 1, vs. second-hand, coded as 0) moderates the relationship between feedback type (exclusivity vs. sustainability) and hubristic pride, with word-of-mouth intentions as the dependent variable. The interaction between feedback type and fashion type on hubristic pride was not statistically significant (b = 0.52, SE = 0.28, t = 1.87, p = 0.06, 95% CI [-0.03, 1.07]). While this does not meet conventional significance thresholds, the direction and magnitude of the effect suggest a possible trend. Thus, an additional analysis was conducted to explore fashion consciousness as a potential covariate, to assess whether including this factor could clarify or strengthen the observed moderation effect.

Another interaction analysis using PROCESS Model 7, incorporating fashion consciousness as a covariate, was performed to further test H4a. This model assessed the moderating effect of fashion type on the relationship between feedback type and hubristic pride, with word-of-mouth intentions as the outcome. The inclusion of the covariate, fashion consciousness, showed a significant direct effect on hubristic pride (b = 0.24, SE = 0.04, t = 5.53, p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.16, 0.33]), indicating its substantial role in the model. Additionally, the interaction between feedback type and fashion type on hubristic pride became statistically significant (b = 0.61, SE = 0.27, t = 2.28, p = 0.02, 95% CI [0.08, 1.14]) explaining 1% additional variance ($\Delta$R² = 0.01, p = 0.02).

Furthermore, the moderated mediation analysis also indicated that the indirect effect of feedback type on word-of-mouth intentions through hubristic pride was significantly moderated by fashion type, with an index of moderated mediation of 0.09 (95% CI [0.01, 0.21]). While the additional explained variance was small ($\Delta$R² = 0.01), the significant p-value (p = 0.02) suggests that fashion type plays a role in shaping the effect of feedback type on hubristic pride. These findings support H4b and highlight the importance of considering fashion consciousness in marketing strategies. The significant interaction effect is shown in Figure 6.

A separate model was run to examine whether the same moderating effect applied to authentic pride. The second model assessed how fashion type (new vs. second-hand) moderates the relationship between feedback type (exclusivity vs. sustainability) and authentic pride, with word-of-mouth intentions as the dependent variable. The model predicting authentic pride was significant (F(4, 389) = 19.93, p < 0.001), accounting for 17% (R² = 0.17) of the variance. However, the interaction between feedback type and fashion type on authentic pride was not significant (b = 0.12, SE = 0.30, t = 0.42, p = 0.68, 95% CI [-0.46, 0.71]), explaining no additional variance ($\Delta$R² = 0.00, p = 0.68). Given the clear lack of statistical significance, as indicated by the high p-value and the confidence interval that comfortably includes zero, further analysis on this interaction was not pursued. This decision is supported by the statistical robustness of the results, which suggest that the interaction effect is unlikely to be meaningful, even when controlling for fashion consciousness. H4b was not confirmed.

General Discussion

The effectiveness of feedback on exclusivity versus sustainability within the context of luxury fashion consumption was empirically tested. The findings reveal that hubristic pride significantly boosts positive word-of-mouth intentions, particularly when feedback emphasizes exclusivity. This effect is more pronounced for new luxury purchases as opposed to second-hand luxury items among fashion-conscious consumers. Additionally, authentic pride also significantly enhances positive word-of-mouth intentions, with particularly strong effects observed. However, feedback that highlighted sustainability did not significantly influence positive word-of-mouth intentions, showing only a marginal tendency towards such an effect. Likewise, the comparison between new and second-hand luxury purchases did not reveal any significant differences in their impact on word-of-mouth intentions. These observations are detailed in Table 2. These findings suggest that while exclusivity remains a powerful motivator in luxury fashion markets, sustainability may require different strategies to similarly influence consumer behavior. This highlights the complex interplay between consumer values and marketing strategies in the luxury fashion sector.

| Hypothesis | Relationship | Effect / CI | Results |

| H1a | Hubristic pride $\rightarrow$ Word-of-mouth intentions | $b = .26$ | Supported |

| H1b | Authentic pride $\rightarrow$ Word-of-mouth intentions | $b = .84$ | Supported |

| H2a | Feedback type $\rightarrow$ Hubristic pride | $b = .26,$$95%CI[.06, .45]$ | Supported |

| H2b | Feedback type $\rightarrow$ Authentic pride | $b = -.11,$$95%CI[-.31, .09]$ | Not Supported |

| H3a | Feedback type $\rightarrow$ Hubristic pride $\rightarrow$ Word-of-mouth intentions | $b = .09,$$95%CI[.02, .02]$ | Supported |

| H3b | Feedback type $\rightarrow$ Authentic pride $\rightarrow$ Word-of-mouth intentions | $b = -.14,$$95%CI[-.38, .11]$ | Not Supported |

| H4a | Feedback type $\rightarrow$ Luxury type $\rightarrow$ Hubristic pride $\rightarrow$ Word-of-mouth intentions | $b = .09,$$95%CI[.01, .21]$ | Supported |

| H4b | Feedback type $\rightarrow$ Luxury type $\rightarrow$ Authentic pride $\rightarrow$ Word-of-mouth intentions | $b = .12,$$95%CI[-.46, .71]$ | Not Supported |

Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the growing body of research at the intersection of luxury fashion consumption, pride, and sustainability. By highlighting the nuanced roles of hubristic and authentic pride in response to feedback, this paper offers key theoretical insights into how tailored messaging influences consumer emotions and behavior in luxury markets.

First, the findings demonstrate that feedback emphasizing exclusivity significantly enhances hubristic pride, which, in turn, drives positive word-of-mouth intentions. This aligns with existing theories associating luxury consumption with feelings of superiority and exclusivity (e.g., Kapferer & Bastien, 2009; Tynan et al., 2010) while expanding on emerging research that links these emotions to word-of-mouth behaviors (e.g., Septianto et al., 2020; Septianto et al., 2022). The study provides further empirical support for the notion that hubristic pride is a key emotional driver in luxury marketing and deepen the understanding of the emotional drivers underpinning consumer advocacy in luxury markets.

Second, this research underscores the dual nature of pride in luxury consumption, revealing that hubristic pride aligns with exclusivity and status-driven appeal, whereas authentic pride is more closely tied to ethical and sustainable aspects of luxury items (Tracy & Robins, 2007; McFerran et al., 2014). While feedback emphasizing sustainability showed a potential trend in enhancing word-of-mouth through authentic pride, this effect was not statistically significant. These findings refine the understanding of pride-driven advocacy in luxury consumption by showing that, although sustainability-focused feedback did not directly enhance authentic pride, authentic pride remains a strong predictor of word-of-mouth intentions. This suggests that authentic pride is an important driver of consumer advocacy, but its activation may require additional emotional reinforcement beyond sustainability messaging alone. Nonetheless, the strong influence of authentic pride on word-of-mouth intentions highlights its potential as a valuable avenue for further exploration in both luxury and sustainable consumer behavior.

Moreover, this study extends previous work on consumer pride (Septianto et al., 2020; Septianto et al., 2020) by applying these concepts to new and second-hand luxury fashion. The findings demonstrate that the effectiveness of exclusivity-focused feedback, mediated by hubristic pride, varies between new and second-hand luxury items. This highlights the complex interplay between product characteristics, consumer emotions, and behavioral outcomes, contributing to theories in luxury marketing and sustainable consumption. It suggests that marketers must tailor their strategies to match the specific type of luxury product and the emotions they aim to evoke, optimizing both engagement and advocacy.

Also, this study extends the insights of (Aleem et al., 2024) by providing empirical evidence on how consumers emotionally respond to exclusivity- and sustainability-focused feedback in luxury fashion. While (Aleem et al., 2024) highlight the growing tension between exclusivity and sustainability in luxury markets, the present study contributes to this discussion by demonstrating how these competing narratives activate different pride mechanisms (hubristic vs. authentic) and, in turn, influence word-of-mouth intentions.

Furthermore, while (Aleem et al., 2024) emphasize the increasing relevance of new and second-hand luxury within the broader transformation of the industry, the findings of this study provide a more nuanced understanding of how consumers experience emotional engagement in these different luxury categories. Specifically, the results suggest that exclusivity-driven feedback more effectively enhances hubristic pride in new luxury purchases, whereas sustainability-driven feedback does not significantly activate authentic pride in second-hand luxury unless explicitly reinforced.

Notably, the non-significant results for H2b, H3b, and H4b suggest that sustainability feedback may not strongly influence consumer emotions or word-of-mouth intentions in a luxury context. One possible explanation is that hubristic pride plays a dominant role in exclusivity-driven luxury consumption, which may have contributed to the non-significant mediation effect of authentic pride (H3b). Since exclusivity is inherently tied to status signaling (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009), hubristic pride may be a more immediate emotional response than authentic pride, potentially overshadowing its effects.

Similarly, the lack of a significant effect of sustainability feedback on authentic pride (H2b) suggests that sustainability messaging may not be as emotionally salient in luxury contexts, where consumers are more accustomed to narratives of prestige and differentiation. This aligns with previous research indicating that sustainability communication in luxury markets often faces challenges in effectively engaging consumers, indicating that sustainability is often perceived as conflicting with the core values of luxury, such as exclusivity and prestige (Aleem et al., 2024).

A possible reason for this misalignment lies in value-framing theory (Schwartz, 1992), which suggests that individuals prioritize values differently. Luxury consumers tend to prioritize self-enhancement values (e.g., status, power, achievement), while sustainability messaging is more aligned with self-transcendence values (e.g., universalism, benevolence, environmental concern). As a result, sustainability-focused messaging may not elicit a strong emotional response in this segment. Instead, exclusivity-based feedback is likely to resonate more effectively, as it reinforces the dominant value orientation within luxury consumption.

This challenge is further compounded by the perception that sustainable luxury products are atypical, as they deviate from traditional luxury associations with abundance and indulgence (Amatulli et al., 2021). While this atypicality can enhance perceptions of uniqueness for certain consumers, it may also create a disconnect for those who primarily associate luxury with status and exclusivity. Furthermore, research suggests that luxury consumers are more receptive to sustainability initiatives when they are positioned as status-enhancing and publicly visible, rather than as internal efforts focused on ethical responsibility (Amatulli et al., 2018). This suggests that the emotional impact of sustainability communication in luxury contexts may be limited unless brands frame sustainability within self-enhancement narratives, such as by emphasizing personal prestige or unique craftsmanship associated with sustainable products.

Additionally, consumer skepticism toward sustainability claims, particularly due to widespread greenwashing practices, may further weaken the impact of sustainability-focused feedback. (Policarpo et al., 2023) found that perceived greenwashing significantly reduces consumer trust in green clothing brands. Their study shows that when consumers believe brands exaggerate or misrepresent their sustainability efforts, trust declines, leading to lower purchase intent. Similarly, (Riesgo et al., 2023) identified lack of trust in sustainability claims as the primary barrier preventing consumers from purchasing sustainable fashion. Their findings indicate that many consumers refrain from buying sustainable products not because they oppose sustainability, but because they struggle to determine whether brands' claims are genuine or simply a marketing strategy. This uncertainty may also discourage consumers from engaging in word-of-mouth communication about sustainable fashion brands. Without sufficient trust, consumers may fear spreading misleading information or associating themselves with brands that could later be exposed for greenwashing.

This skepticism is particularly relevant as trust in sustainability claims has recently been shown to play a crucial role in fostering authentic pride (Arnesen et al., 2024). Arnesen et al. (2024) demonstrate that the level of trust consumers place in a brand’s sustainability efforts is strongly influenced by how concrete the brand’s messaging is. When sustainability claims are clear and specific consumer trust increases, which in turn enhances authentic pride. As a result, consumers become not only more willing to purchase sustainable products but also more likely to share their positive experiences and recommendations with others. This suggests that credibility, built through trustworthy communication, is essential for maximizing the impact of sustainability-focused feedback.

Lastly, H4b, which proposed that sustainability feedback would be more effective for second-hand luxury purchases, was also not supported. This suggests that although second-hand luxury is often positioned as a more sustainable alternative, consumers may not explicitly associate their purchase decisions with sustainability unless this message is particularly strong. Instead, second-hand luxury consumption may be driven more by factors such as economic value or rarity, rather than sustainability concerns. This highlights the need for brands to reconsider how sustainability is communicated in second-hand luxury markets, potentially integrating elements of exclusivity, craftsmanship, or longevity to make the sustainability aspect more appealing to consumers.

These theoretical contributions underscore the enduring appeal of exclusivity as a motivator in luxury markets while highlighting the growing need to integrate sustainability in ways that resonate with consumer emotions and cultural values. By bridging these elements, the luxury fashion industry can evolve toward more sustainable practices without compromising the allure that drives consumer desire.

Managerial Implications

The study offers actionable strategies for luxury brands seeking to navigate the dual demands of sustainability and exclusivity. First, the findings demonstrate that feedback emphasizing exclusivity significantly enhances hubristic pride, which, in turn, drives positive word-of-mouth intentions. This highlights the importance of maintaining exclusivity as a central element of luxury brand communications, particularly for new luxury products. Brands can leverage this insight by designing post-purchase messages and advertising campaigns that emphasize exclusivity and social differentiation, reinforcing the consumer’s sense of status and achievement. Such strategies not only encourage brand advocacy but can also strengthen consumer loyalty by deepening emotional connections (Berger & Milkman, 2012), which are particularly crucial in highly competitive luxury markets where differentiation and brand identity are key drivers of long-term success.

Second, this research underscores the need for differentiated communication strategies tailored to the type of luxury product. Exclusivity-focused messaging resonates strongly with consumption of new luxury products, particularly among fashion-conscious consumers, while the findings suggest that sustainability messaging has a more limited effect. One possible explanation is that sustainable luxury products are often perceived as atypical within the luxury sector, as they do not fit the traditional associations of luxury with excess and exclusivity (Amatulli et al., 2021). While this atypicality can enhance perceptions of uniqueness for certain consumers, it may also create a disconnect for those who primarily associate luxury with status and prestige. These results imply that brands must carefully tailor messaging to resonate with the values of specific consumer segments, in order to foster engagement.

The non-significant effect of sustainability-focused feedback on word-of-mouth intentions highlights the challenges brands face in effectively integrating sustainability messaging without diluting the aspirational appeal of luxury products. However, sustainability remains an important avenue for appealing to environmentally conscious consumers, particularly in second-hand luxury markets, where notions of timeless quality and durability play a more central role. Given sustainability’s link to authentic pride, brands should consider framing sustainability in ways that align with exclusivity, such as emphasizing rarity, craftsmanship, or the longevity of materials, rather than focusing solely on ethical responsibility. By strategically positioning sustainability, brands can preserve the allure of exclusivity while fostering engagement with sustainability-conscious consumers.

By adopting these strategies, luxury brands can better navigate the growing demand for sustainability while preserving their core value of exclusivity, positioning themselves for long-term success in a dynamic and segmented market.

Limitations and Future Research

While this study provides valuable insights into the dynamics of pride and feedback in luxury fashion consumption, it is not without limitations. These limitations present opportunities for future research to expand and refine the findings presented here. Firstly, although the study examined the effects of sustainability-focused feedback, the lack of significant findings may suggest that the communication of sustainability attributes could be improved. Future research should explore other feedback framings, connected to communication of sustainable product, such as concrete versus abstract information. For instance, detailed environmental impact metrics or third-party certifications could enhance consumer trust and engagement. This is particularly relevant given the prevalent skepticism around greenwashing in the fashion industry.

Secondly, the study primarily focused on feedback types and their effects on pride and word-of-mouth intentions. Although the covariate of fashion consciousness was tested and found to have a significant impact in the relationship of feedback focused on exclusivity in new luxury purchases, other covariates, may be more suitable when examining the impact on feedback focused on sustainability in second-hand luxury purchases. Exploring other consumer traits, such as environmental values, or personal ethics, could play significant roles in this interaction. Future studies could investigate how these covariates mediate or moderate the observed relationships.

Thirdly, while this study finds a significant effect of exclusivity-focused feedback on hubristic pride, the variance explained (1.6%) is modest. However, small effect sizes are common in psychological and consumer behavior research, particularly in experimental studies where manipulations rarely account for large portions of variance (Richard et al., 2003). Prior meta-analyses have shown that social psychological experiments often report effect sizes in the range of r = 0.21, corresponding to an explained variance of approximately 4.4% (Richard et al., 2003). The effect size in this study (r = 0.126, corresponding to R² = 1.6%), is smaller but remains within the range of meaningful effects. Even small effects can have practical implications in marketing and consumer psychology, where multiple interacting factors shape decision-making (Aguinis et al., 2005). Future research could explore additional moderators, such as individual differences in status motivation, materialism, or brand attachment, to better understand the broader mechanisms influencing hubristic pride and word-of-mouth intentions.

Fourthly, this study does not include measures of income or prior ownership of luxury fashion, which could potentially influence how consumers respond to exclusivity- and sustainability-focused feedback. However, as luxury fashion becomes more accessible and the second-hand market expands, the relevance of these factors may be shifting. On the one hand, prior experience with luxury fashion and higher disposable income could amplify the impact of exclusivity-driven messaging. On the other hand, the growing democratization of luxury and the increasing prevalence of second-hand consumption may reduce the importance of financial status in shaping consumer responses. Future research could explore how these socioeconomic factors interact with emotional drivers such as pride to provide a more nuanced understanding of consumer behavior in luxury fashion.

Additionally, this study's findings are based on a U.S. sample, which may limit their generalizability across cultures. Cultural norms shape both luxury consumption and emotional responses to exclusivity and sustainability (Septianto et al., 2020). In individualistic societies like the U.S., luxury is often linked to personal distinction and status signaling, aligning with the hubristic pride pathway identified in this study (Kapferer & Bastien, 2009). In contrast, collectivistic cultures, such as China and Japan, emphasize luxury as a means of reinforcing social belonging and in-group prestige (Wong & Ahuvia, 1998). Given the growing importance of emerging luxury markets in collectivistic societies, countries like China and India represent significant opportunities for luxury brands (Khan, 2015). However, consumer perceptions of exclusivity and status-driven consumption in these regions may differ considerably from Western norms, highlighting the need for further research.

Beyond the individualism-collectivism divide, luxury consumption norms also vary within Western markets. While American consumers often associate luxury with status and personal success, European markets emphasize heritage, craftsmanship, and authenticity (Chandon et al., 2016). Given the varying cultural connotations of pride and luxury, future research should examine these dynamics across different cultural settings. For instance, exclusivity may resonate more strongly in American markets, whereas sustainability aligns better with European consumer values, where luxury fashion is often communicated as authentic rather than exclusive (Septianto et al., 2020). These differences may also extend across gender and other consumer segments, such as younger, price-sensitive, or less environmentally aware individuals.

Finally, this research is centered on the luxury fashion market. Comparing luxury with non-luxury fashion segments could provide insights into whether the observed effects of exclusivity and sustainability feedback on pride are unique to luxury or applicable across various market tiers. Given that luxury is deeply connected to exclusivity and carries significant symbolic value, sustainability feedback may be perceived as more trustworthy and better suited to the high-end fashion market. Like luxury, high-end fashion plays a crucial role in the second-hand market, where its association with quality and durability. The intuitive connection to sustainability may be more trustworthy in high-end fashion, as it is less disrupted by the overwhelming symbolism associated with luxury. Such comparisons could also shed light on how consumer perceptions differ across fast fashion, high-end, and luxury, offering a broader understanding of the interplay between product type, feedback, and consumer behavior.

By addressing these areas, future research can build upon the current findings, offering deeper insights into how feedback mechanisms can be optimized to promote both sustainable and luxury fashion consumption.

Funding Statement

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of Interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References